24 October–28 November 2025

“The Elephant Table Exhibition” brings together a group of artists who each temper the picture world through compositions that sit at a slight kilter. As such, currents of strangeness proliferate at different frequencies, subject to the author’s discretion. Perhaps the exhibition’s title can provide a bit of a clue to the stochastic nature of the works on view. Pulled from an aggregated collection of songs, The Elephant Table Album: a compilation of difficult music was assembled in 1983 by the writer Dave Henderson. The result of his endeavors is a haunted sonic landscape Frankensteined together from electronic noises, industrial pulses, and experimental sound play. A similar compiling effort happens here, as disparate practices are brought into tandem. There is no discrete generic undercurrent; instead, overlapping considerations rear their heads. Instead, it presents as an exercise in producing sensational alliances–affinities that firm up over time.

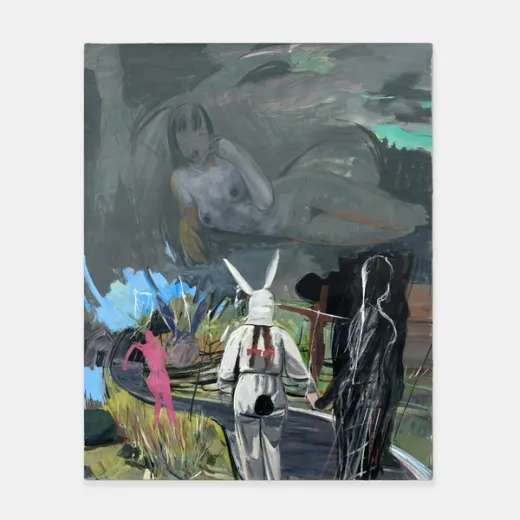

Two new paintings by Christine Burgon operate as continuations of her amalgamated referentialpursuits. In Mad Season a bunny suited figure leads a sketched out form along some ambiguous path. Upon further inspection, new elements start to reveal themselves. For instance, a crucifixion is staged at the roadside and another bunny form lingers just beyond it. The image’s top half is occupied by a subject in recline, which serves as an interruption to the bucolic lower scene. Interior and exterior are folded into one, accented by scattered gestural and nonobjective marks. Another painting, titled I Need Your Life, was completed at the same time. Fittingly, its palette is compatible to that of Mad Season, though here Burgon mostly clings to abstraction. The multimedia composition is a collage of nearly there forms like a smiling dog head, rotating angels, and Mickey Mouse alongside total non-representational expanses. The painter is questioning how much the subject matter should be articulated, and where it can slip into pigmental oblivion.

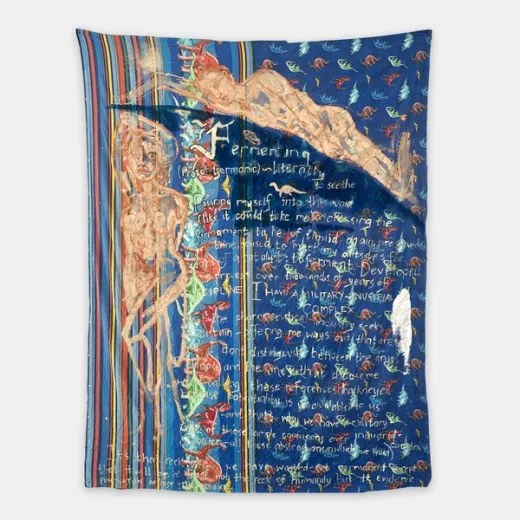

Similarly, Grace Anderson’s symphonic compositions are the result of an ongoing plot to mine and arrange visual materials from all over the place. Here, Anderson’s wandering temperament results in curiously networked aspects that swirl and crash against one another. The resulting quasi-identifiable ephemera comes out from her allegiance to a largely deskilled territory, where the autobiographical and imaginary go to be optically reupholstered. Abstracting, enmeshing, and destroying are all negotiated within the same picture plane. Anderson exists in a post-Guston, post-Sillman climate of thinking-through-painting, where particularly buoyant forms rise to the top and everything else falls away into the ether of gesture, color, and shapes that resist definition.

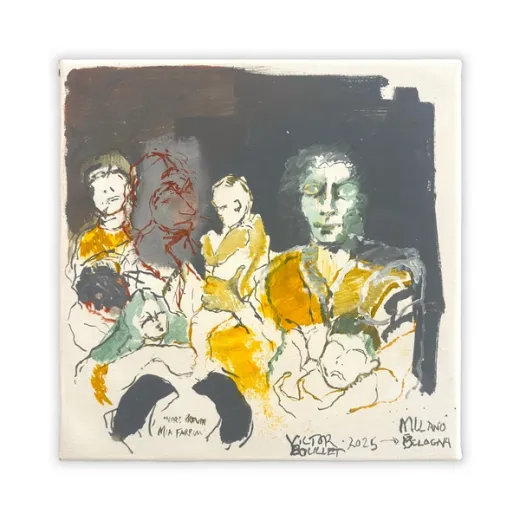

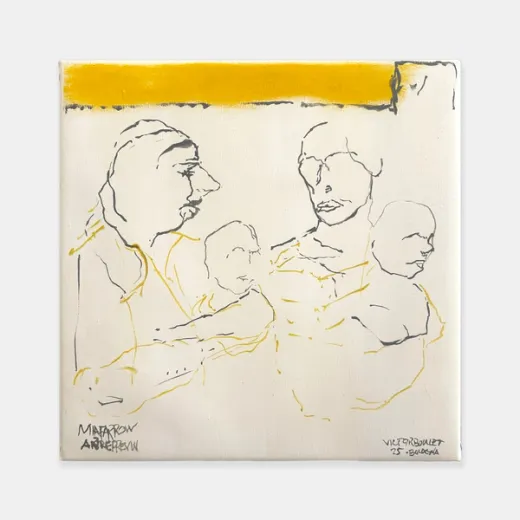

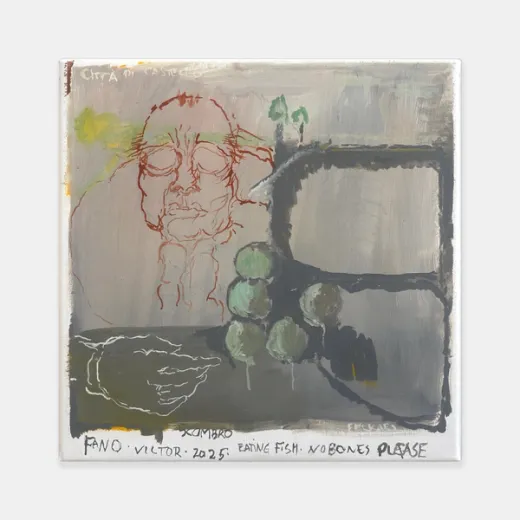

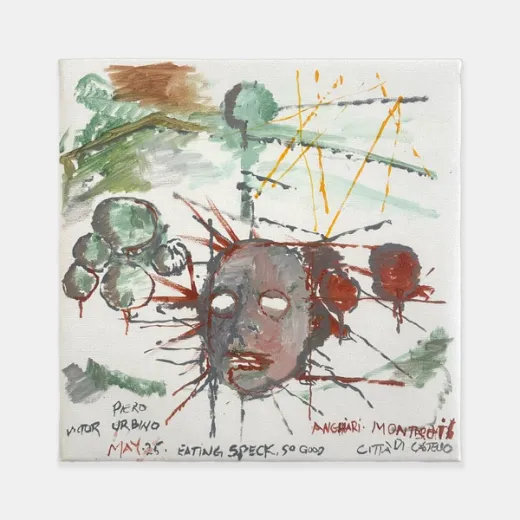

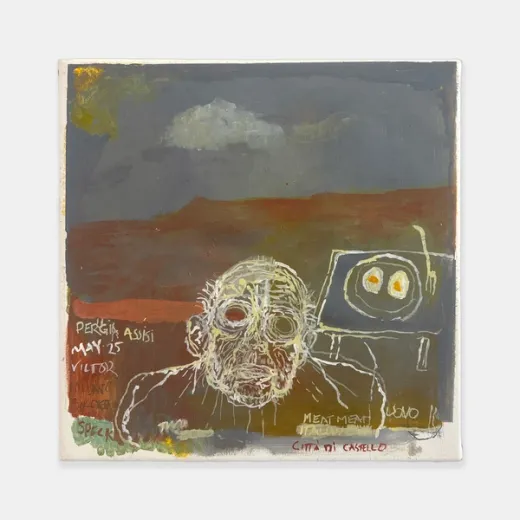

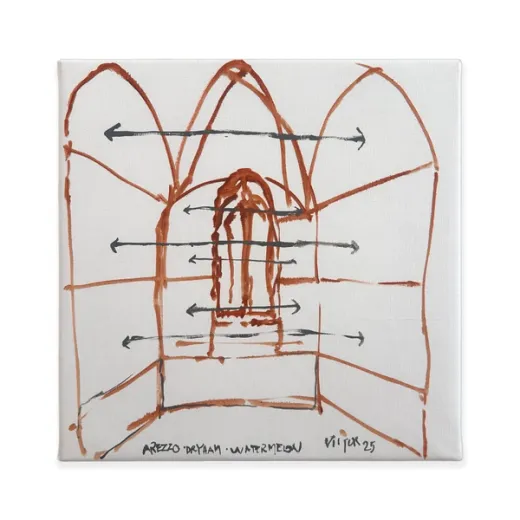

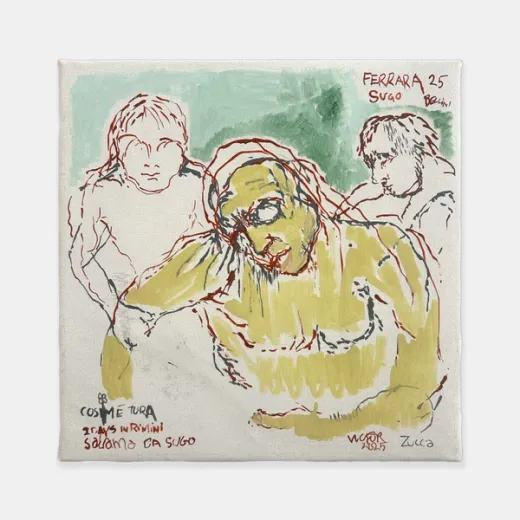

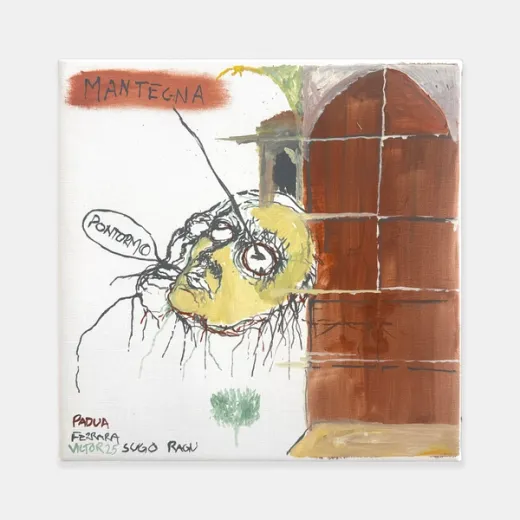

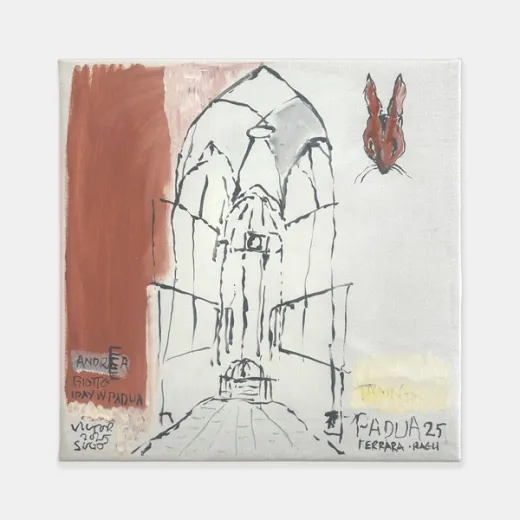

Victor Boullet also swoops in on the semi-representational front. Paintings from a recent series fall right in line with the artist’s knack for splintered compositional structures, as he pools together resources from his world and those from history. To spark a new body of work, there needs to be an “in,” or, and access point through which Boullet can then take over and flood the canvas with his subjective frequencies. For this particular compositional sequence, Mia Farrow and André Previn’s relationship and children are the root. Taken together, abstracted, and then expanded upon, these conditions are converted by Boullet into raw material available for distortion. Formally, the work has gotten looser, with threads of the artist’s drawing practice filtering in–mistakes and all. A recent pilgrimage across Italy manifests itself in textual scrawlings, aspects from historical artworks, and architectural elements from the The Renaissance homeland.

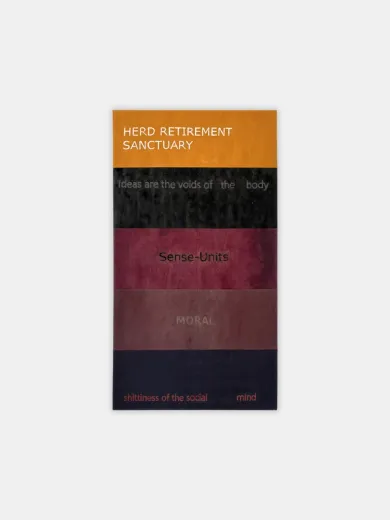

Josey Kidd-Crowe’s abstractions exist in a markedly less representational space. There’s a de Kooningesque freedom in some of his newer works, whereas clearer signifiers abound in earlier ones. He also incorporates text, though linguistic meaning and grammar are upended. Instead, Kidd-Crowe treats letters and words as open material to be manipulated through compositional structure and painterly urges. A press release for his 2020 exhibition at West Space Offsite in Melbourne aptly characterizes his output, asserting that his works “expose the process of painting without falling into reductionism.” It becomes clear, then, that Kidd-Crowe continues to refine a system through which unbidden source material is molded into a discrete pictorial ecosystem.

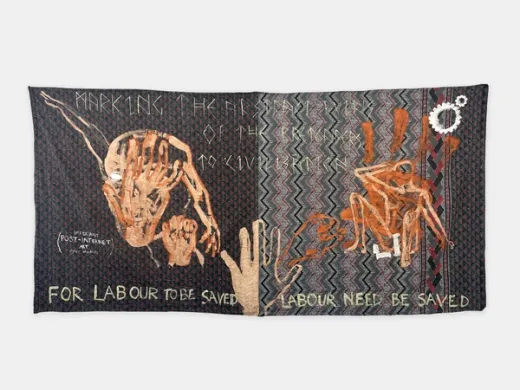

Two works plucked from Zoe Marni Robertson’s “Various Protest Banners" series serve as strong examples of the artist’s investments in politics, sustainability, and painting’s history. Here, she wrestles with the labor of building a composition and how the final form might stand as an act of resistance. Marni Robertson inherits the patterns of these bedsheets, an effort that recalls Sigmar Polke’s “Stoffbilder” series, in which found textiles provide support as image, reference to commercial manufacture, and a nod toward the domestic. She indulges the rawness of the material and its inherited patterns as a means to buck the weirdness of technocracy. Meaning—the ultimate world for Marni Robertson is one that can be felt. It’s wrought with a dimensionality unbeknownst to the digital space. Textures of yesteryear are reupholstered to demonstrate the merit of being-in-space.

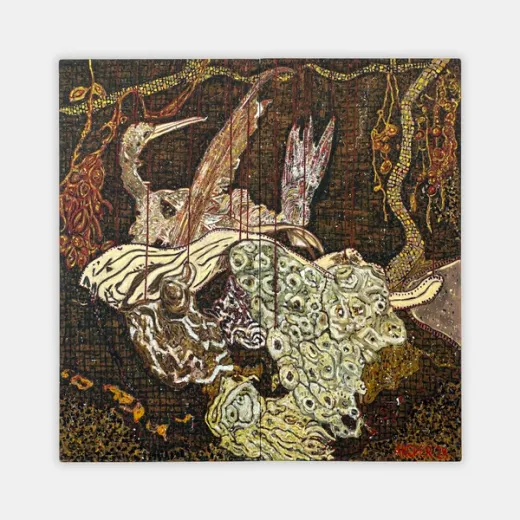

Finally, Suzanne Archer’s Beachcombing South Coast is a wonderful ode to her Australian context. Art critic Rex Butler reflects on Archer’s late work kindly, writing that it communicates “a certain relief from the stress of constantly having to innovate, a pleasure in the assuredness of their own mastery, an enjoyment in drawing upon the credibility so assiduously built up over so many years.” Ruminations on life and nature characterize this painting, as she refers to a coastal landscape in sumptuous earth tones.

Replete with imaginal mash-ups, spiritual meanderings, and clustered abstractions, the works in “The Elephant Table Exhibition” collide and tangle up in networks of painterly impulse. While there exists no singular connective tissue, there are subtle branches between each oeuvre that serve as points of resonance–from diaristic meanderings to subcultural recapitulations.

Reilly Davidson - US based curator / writer