7 December 2024–11 January 2025

Amorous Envy is the name of the lipstick worn by the shop assistant in Tim Hardy’s short film, Vanity Torso Animal Spirit. “It really suits you,” says the shopper in the dialogue that shifts power and seduction between the two women; a back and forth of compliments, coy invitation and false refutation. At one point the two women look towards us, just right of the camera, as though at a changing room mirror; at themselves and each other in a Persona-like telescoping. A ‘whirligig’ is how Jean-Paul Satre describes the binding of appearance and reality mastered by Jean Genet; two poles spinning ever more tightly together. In his introduction to Genet’s twin plays, The Maids and Deathwatch, Satre describes the writer’s circular sophistry as a knowing indulgence in false reasoning. The artificiality of theatre is what attracts Genet to the form, and in The Maids he ushers in artifice by determining that men play the two maid characters, who play at being each other and play at being their mistress. In their game, the maids are always other than themselves and haunt one another with duality. Our intuition that when artifice falls away it reveals true being is taunted by Genet, who layers artifice on artifice to reveal nothingness. The shop assistant in Hardy’s film recalls the various hair colours she has had over the years, deciding what will come next in the long line of shifting appearances.

The psychoanalytic potency of appearance and of mirroring runs through Hardy’s photographs, shot at sites including a modeling school, an improvisation class, back of house at a theatre, a prop store, a clock repair workshop and a violin making studio. Hardy’s work nods to the circular logic of Victor Burgin’s Fiction Film 1991—a series of photographs masquerading as stills from a non-existent film adaptation of Andre Breton’s 1928 book, Nadja. Breton’s book expresses the central ideas of Surrealism through the semi-fictive story of the writer’s encounter, and short-lived affair, with a woman in the streets of Paris. She is based on a patient of Pierre Janet, a psychotherapist who made contributions to understandings of dissociation and traumatic memory. Burgin’s work, sixty-three years after Breton’s book, operates through ciphers; photographic stills of an imagined film adaptation of an actual novel weaving a fiction about a real-life psychology patient.

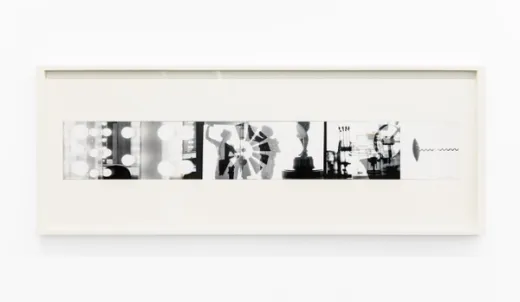

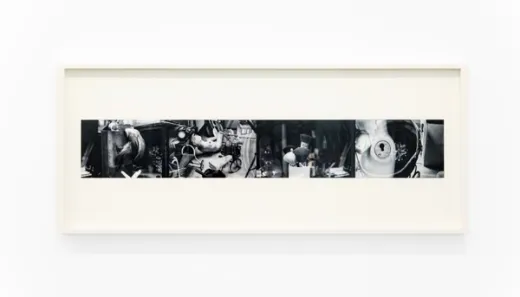

Hardy’s images imbibe this circular logic. They contain narrative clues to nowhere in particular and, with their peculiar specificity, allow the mind to concoct possible scenes and dramas. The black and white composite images invoke surrealist juxtaposition drowsy with symbolism that refuses to attach itself; a clock in pieces, a bunch of feathers, a dressing room mirror. They stretch horizontally with a filmic condensing of time and the implied progression of narrative. The outside-the-frame suggestiveness is especially potent in an image of a hirsute leg resting on a coffee table near a bunch of flowers as white as its white sport sock. The folds of the leather couch and the bent knee make dark creases alluring in the context of the spotless and unremarkable air bnb-esque room.

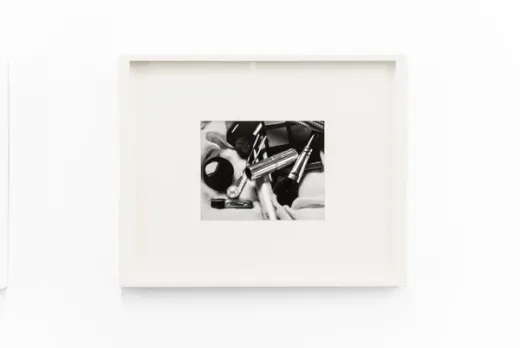

In other tableau arrangements, objects bear a similarly associative fecundity: smashed instruments, the complex internal mechanism of a timepiece, the spilled contents of a makeup bag. Often, the images kaleidoscope time or space, as in Playing House. The tiny rooms of a doll’s house are crammed with precise and uncannily realistic miniature objects, skewing our sense of scale in a nauseating perversion; a mimesis of the interior decorating choices and eccentric collecting habits of an unknown character, all rendered in a controllable format and scale.

The evanescence of the series speaks to Hardy’s interest in Robert Altman’s beguiling 2005 advertisement for Revlon. The cast includes Eva Mendes, Halle Berry, Julianne Moore, Susan Sarandon and Kate Bosworth.

The actresses play themselves in a dressing room scene following an unspecified performance. As they change out of gowns, amongst a dizzying array of mirrors and reflections, they talk laughingly about ‘nothing’; their nothing plans for the evening, the pleasure of doing nothing, ‘it takes time to do nothing’. On it goes, in a tranquilising repartee, accompanied by British electronica outfit Bent’s track, Beautiful Otherness (which in the pop-bliss mix sounds a lot like ‘beautiful nothingness’): “Beautiful otherness, love you because of this, lost in the loveliness…” The ad is a 1 minute 30 second confection: together, a film director, a cast of stars and a beauty conglomerate make nothing. Altman uses the artifice of commercialism to his own ends to speculate on femininity, posture and poise. It recalls Genet’s emptying of femininity in The Maids, so that it becomes a symbolic affect that can be put on and off by anyone. The trappings of femininity—the make up being marketed, the gowns, the postures—are nothing, as in, they are unattached: free-floating signifiers

The opportunity to parse femininity through the commercial form is also taken up by David Lynch in his 2010 short for Dior, Lady Blue Shanghai, staring Marion Cotiallard in a 1940s suit and featuring a Lady Dior handbag in blue patent leather. The film has the hallmark surrealism and shadowy glamour of Lynch’s feature length psychological thrillers. Here, the handbag-talisman unlocks Cotiallard’s repressed memories of a lover from a past life.

Sublimated desire and the internal struggle in the feminine subject is the essence of the first act in Hardy’s film. He too employs the mannered artifice of the commercial as a framework, though it is the chamber theatre piece that is more present as genre in his two-part film. The pristine shop where Hardy sets the first act, itself a set for selling clothes, compresses all three women, shop assistants and shopper alike. Deferral is the name of the game. The only channel for libidinal energy is the talkative assistant who eventually undoes the tense shopper with a frisson. Flirtation as a sales device is sickly delicious and then quickly disorientating, as anyone who has been wooed into trying on too-glamorous clothes and then showered with disingenuous compliments knows. The shopper protagonist crumbles, a silent break, sent over the edge, ostensibly by a lost key or wallet.

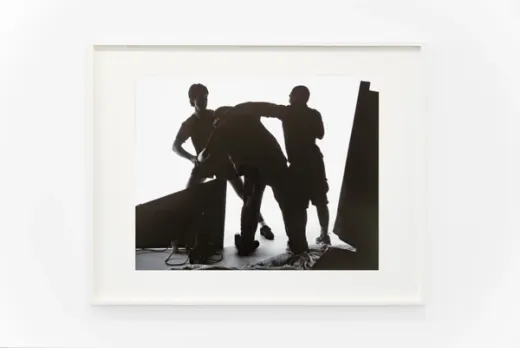

The struggle of sublimation in this first act is balanced by the unchecked release of violent desire in the second act. This half of the film follows a group of teenage boys having a morning-after disagreement about a muck-up prank gone wrong. They throw the blame around like a hot potato. The adolescent hazing ritual functions here as the uninhibited space for urges to emerge. One teen says ‘fuck’ with the frequency and zealousness of a person not fucking. Homoeroticism and homophobia swirl around in this Dionysian counterpart to the Apollonian order of the retail scene.

In reference to the dynamic he establishes between the three teenagers, Hardy cites Wilfred Bion’s Experiences in Groups and other papers, written in the 1940s, which synthesises Bion’s psychoanalytic studies and clinical observations of such group dynamics. The analyst describes how anonymity within a group creates disinhibition and a variety of antinormative collective behaviors such as violent crowds and lynch mobs, and presumably muck-up pranks. Indeed Hardy’s stage, with its single minimal set à la Dogville, provides the format of clinical observation, as though we watch through a one-way mirrored window. The chamber piece as a format evokes a kind of observational microscope onto its subjects. The soporific headiness of the droning soundtrack and the starkly silhouetted actors locates us in the “theatre of the mind”, as Freud called dreams. A zone where repressed wishes can be examined through the analytic lens. In both parts of the film, multi-directional desire overwhelms the protagonists; be or be with, love or destroy. Contradictory impulses and neuroses concertina, as in dreams where anxieties and fantasies are compressed. The same applies to Hardy’s exhibition holistically, where the distinction between fiction and documentation is disregarded in favour of the metaphorical potency of both. As with morning analysis of an unsettling dream, metaphorical excavation of Hardy’s works will go as far as we are willing. At the same time Hardy plays with affect (particularly in relation to constructed femininity) to generate an enigmatic tension between laden symbolism and airy artifice. Gazing into a mirror in the Revlon ad, Eva Mendes coos, ‘Nothing is always something.’ - Pip Wallis

Film Credits

Starring: Penelope Burke, Pasha Lukovic, Anna Sun, Athan Vlahogiannis, Moss Lasica-Wood & Alexander Sheehan.

Writers: Tim Hardy, Ignatz Cady-Freer & Penelope Burke

Executive Producer: Antuong Nguyen

Production Company: Silky Jazz Films

Showcard Design: John Paul Patrikas

Accompanying Essay: Pip Wallis

Cinematographer: Gabriel Francis

Original Score: Sarah McCauley

1st AC & Production Assistant: Victoria Vo

1st AD: Chi Tran

Sound Recordist: Conor Whitty

Gaffe : Francis Healy-Wood

Art Department: Alexis Kanatsios

Art Department Assistants: Chelsea Young & Hugh Crowley

Hair and Beauty: Georgia Gaillard

Wardrobe: Blake Barns

Wardrobe Assistant: Maleka Karly

BTS Photography: Rebecca Martin

Set design includes: They are, aren’t They?, 2020-24 by Lewis Fidock & Joshua Petherick.

Post & Artwork Production

Editors: Antuong Nguyen & Tim Hardy

Video Artwork Fabrication: Hugo Blomley

Framing Fabrication: Georgia White and Luke Ingram at Arten Fine Art Framing

Framing Assistance: Chelsea Young, Dan Price, Levi Franco & Matthew Asling at Arten Fine Art Framing

Scanning Lab: Echo Darkroom

Tape Transfer: TapesToDigital

Monitor Hire: 56K Records

Post-Production & Install Assistance: Hamish Hardy, Chelsea Young, Hugh Crowley & Netta Talmi

Supported by the Midsumma Regional Activation Program