10 February–10 March 2023

This exhibition takes its cue from the history of the NAP Contemporary building, which used to be a Volkswagen salesroom established by NAP co-director Riley Davison's family. The exhibition includes a range of sculptural and wall-based works that reference the form of a car: Burchill/McCamley present two customised car seats with steel bases; Alexandra Peters has included a suite of shaped canvases based on the car doors of Subaru’s Forester line; and Lauren Burrow’s works—originally shown in Milani Gallery’s Carpark Gallery in 2019—are a plaster-cast of a three-metre-long scratch made by a car key (a 1978 Toyota Corolla) and a number of car windows sourced from wrecking yards, which Burrow has embellished with bioglitter and rhinestones.

An exhibition of car parts may bring to mind English author J.G. Ballard’s 1970 Crashed Cars exhibition, where he presented three wrecked cars (a Pontiac, an Austin Cambridge A60, and a Mini borrowed from Charles Symmonds’ Motor Crash Repairs) as found objects at New Arts Lab in Camden Town, London. Ballard conceived the exhibition while he was working on his famous 1973 novel Crash (adapted to film by David Cronenberg in 1996), which examines the car as an icon of 20th-century culture: a symbol of individualism and atomisation, consumerism and mass-manufacture, speed and intensity, sexuality and death. Crash, the novel, was preceded by the chapter ‘Crash!’ in Ballard’s experimental book of ‘surgical fiction,’ The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), from which this exhibition borrows its title.

I hired a topless girl to interview people on closed-circuit TV. The violent and overexcited reaction of the guests at the opening party [of Crashed Cars] was a deliberate imaginative overload which I imposed upon them in order to test my own obsession. The subsequent damage inflicted on the cars during the month of the show—people splashed them with paint, tore off the wing mirrors—and at the opening party, where the topless girl was almost raped in the rear seat of the Pontiac (a scene straight from Crash itself), convinced me I should write Crash. The girl later wrote a damningly hostile review of the show in an underground paper.

Several of the works in Mildura Atrocity Exhibition channel the latent violence of the car, though in slightly different ways to Crash. Burrow’s scratch Negative content (2023) speaks to the history of improvised weapons and prosthetics: of growing up being told to wedge keys between her fingers when walking home late at night. The scratch is an elemental expression of the subject, like the handprint or petroglyph, but it’s also a classic form of vandalism against private property. Negative content is installed low on the wall below waist-height, to indicate surreptitious execution.

The engineers waved to the crowd reassuringly and moved towards the motorcycle, which lay on its side fifty yards behind the car. They began to pick up the sections of the cyclist’s body, tucking the legs and head under their arms. Shavings of fibreglass from its face and shoulders speckled the glass around the test car like silver snow, a death confetti … Helen Remington held my arm. She smiled at me, nodding encouragingly as if urging a child across some mental hurdle. ‘We can have a look at it again on the Ampex. They’re showing it in slow-motion.’

The form of Burchill/McCamley’s works Figure A (2016) and Autorecliner (2015)—free-standing car seats liberated from their ‘mobile cockpits’—are reminiscent of crash-test dummies. Figure A also references 20th-century Dutch designer Gerrit Rietvield’s famous zig-zag chair (1934) through its steel base, as well as Marcel Broodthaers’ Musée d’Arte Moderne Department des Aigles (1972) via its taxidermied pigeon perched on the black leatherette seat. The pigeon, however, is the inverse symbol of Broodthaers’ eagle, the latter of which appears in so much heraldry—it being a hunting bird associated with leadership, vision, and thus powerful families and nations. The pigeon, by contrast, is decisively common—maligned by property owners who install pigeon spikes to deter their nesting. If the eagle connotes blue skies and mountain ranges, the pigeon connotes concrete and steel postindustrial areas (like carparks and warehouses) that are hostile to most other forms of life.

The enormous energy of the twentieth century, enough to drive the planet into a new orbit around a happier star, was being expended to maintain this immense motionless pause.

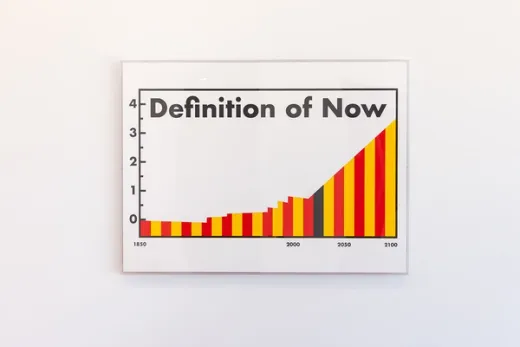

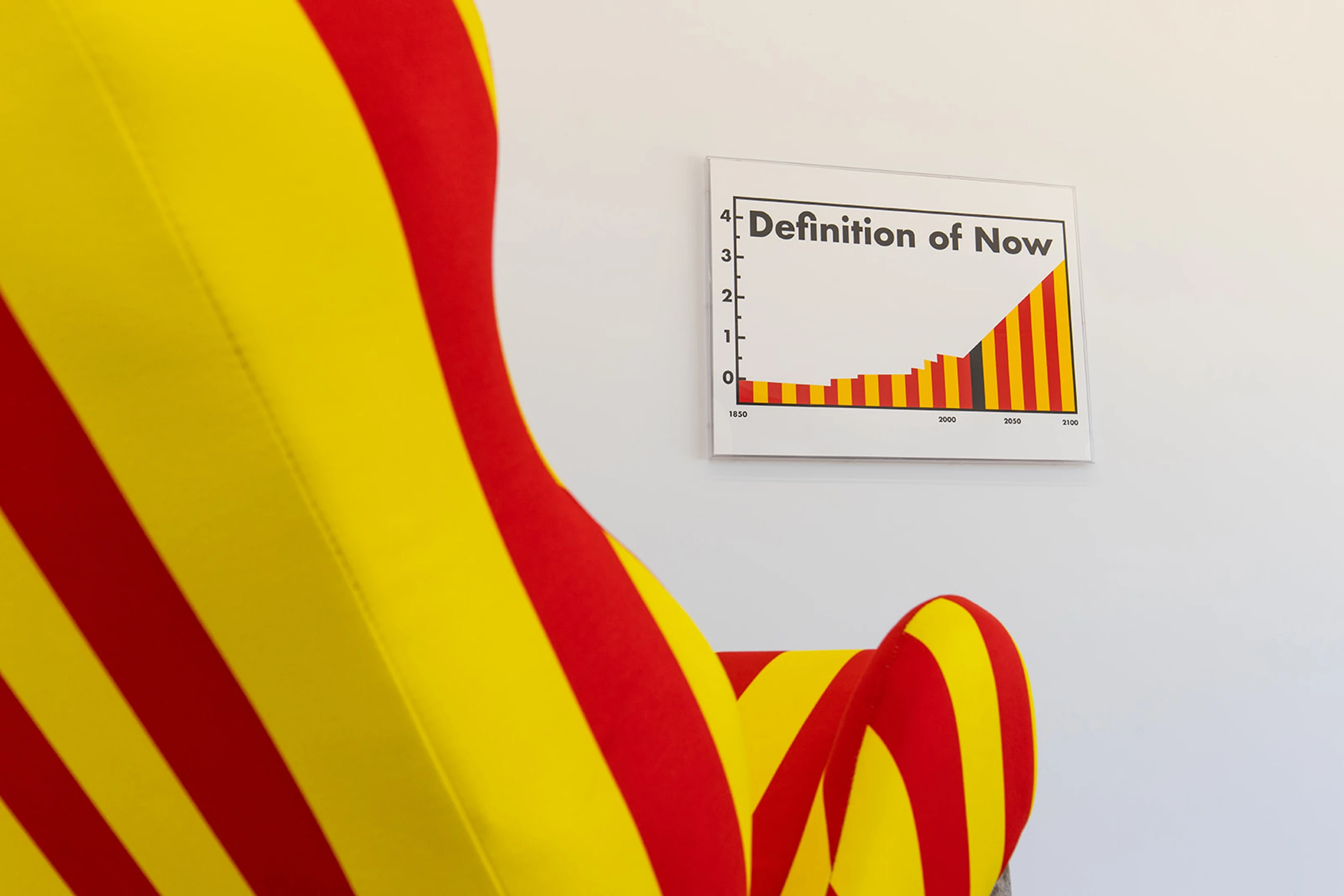

Against the instant death and violence associated with car crashes, Autorecliner invokes the slow death of climate crisis. Its red and yellow stripes (a colour combination often used to denote hazard) are both a nod to Daniel Buren’s orange and white stripes as well to an ascending graph that charts the annual global temperature increase since the beginning of the industrial revolution, projected up to the year 2100. This graph is reproduced in the 2021 screenprint, Definition of Now. Like the annual global temperature as shown on the graph, the striped car seat is poised to catapult off the top of an ascending steel ramp. Together, the car seat and graph point to a different kind of death to Ballard’s twentieth-century car crash victims: the slow suicidal march of anthropogenic climate warming, intimately entwined with the burning of fossil fuels such as in petrol-fuelled cars.

Petroleum consumption is also referenced in Burrow’s car window works Exiguous plains (2019), which are coated in a resin film with bioglitter made from cellulose extracted from eucalyptus leaves. The shimmering colours of the bioglitter reference nail varnish, drawing parallels between the car windows and fingernails—both prosthetics, an extension of the body. In bringing cellulose from eucalyptus and plastic car parts together, Burrow also invokes the long time scale of petroleum (extracts of which are used to make a range of plastics, including car paint and nail polish), the crude oil made from the compression of fossilised animal and plant matter over millions of years. As a result of petroleum’s origin in organic matter (like eucalyptus forests), it stores large amounts of carbon that is released back into the atmosphere when it is burned (i.e., in the engines of cars.)

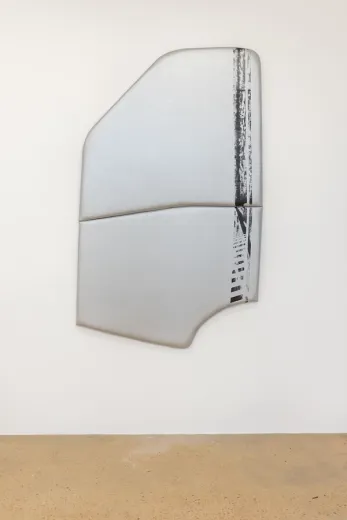

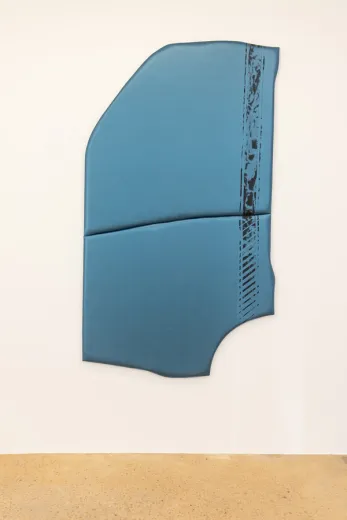

As with Burrow’s conjoining of the car paint job with the manicure, a consciously femme identification courses through other works in this exhibition. Alexandra Peters’ Subaru Forester series (2023) is based on the car door of her own Subaru Forester—a line of 4WD that has been historically associated with and marketed to women, single mothers, and lesbians. (In a famous ad campaign in the 1990s, Subaru gave the Foresters number plates like ‘CAMP OUT’ and ‘XENA LVR.’)

The Subaru Forester series connotes the shaped canvases of Kelly or Stella, but departs from these investigations into colour and shape through the use of the nontraditional material of vinyl in lieu of canvas. Peters does not apply pigment to the surface of her paintings in a humanistic way, but rather uses the materials and means of mass industry. She screenprints imagery onto prefabricated imitation leather that she has selected from thick colour swatches that lie around her studio. The seriality of the doors, which morph subtly in each new generation of the Forester, similarly connote mass production. Against a logic of a unique subjectivity that is indivisible from the painting, what Isabelle Graw would describe as its ‘liveliness,’ Peters instead speaks of her works’ capacity to be wiped clean—to be fingerprint-less, to completely remove the artist’s hand. This wipe-downability explains the prevalence of materials like vinyl in hospitals and the taxis, which require constant sanitisation.

The plastic laminates around me, the colour of washed anthracite, were the same tones as her pubic hairs parted at the vestibule of her vulva. The passenger compartment enclosed us like a machine generating from our sexual act an homunculus of blood, semen and engine coolant.

Peters’ Beirut by the Bay (2023) is a large wrapped vinyl diptych. The top half is screenprintedwith a drawing the artist made using bitumen along with distorted found images, and tilts away from the wall to impose on or even cocoon the viewer. This tilt is achieved through Peters’ novel hanging mechanism of attaching crowbars to the backs of her paintings, which then hang off screws in the wall—as if the painting is poised to remove the very hardware that supports it in a gesture of self-erasure. Here, the crowbar hanging mechanism also gives the large rectangular painting the impression of a popped bonnet or car boot.

Mildura Atrocity Exhibition can be read as a dissected car with the constituent parts separated out for display: the windows, seats, doors, paint, bonnet, or boot. In this sense, the technology of the car is presented not as a prosthetic extension of the body with the illusion of unity that bodies entail, but rather, as Jean Baudrillard once wrote of Crash, as ‘the deadly deconstruction of the body … a body with neither organs nor organ pleasures, entirely dominated by gash marks, excisions, and technical scars—all under the gleaming sign of sexuality that is without referentiality and without limits.’

-Helen Hughes

Photography courtesy Vision House Studios, Mildura.